Community Archaeology at Humåtak

Growing Together

San Dionisio & Humåtak

On March 6, 1521, CHamoru people encountered Europeans for the first time when they visited the Magellan expedition that had anchored in their waters while circumnavigating the world. However, the permanent colonization of the Manislan Mariånas (Mariana Islands) begun much later, in 1668. Since then, dramatic changes were to take place, especially after La Reducción was implemented and native CHamorus were forcibly nucleated in a reduced number of villages or towns mainly in the south of Guåhån (Guam).

“Grande rue d’Umata, Ile Gouaham”, Dumont d’Urville 1846

Fort Soledad, 2019

Humåtak, one of the most significant villages during pre-colonial Latte times, became one of the main reducciones in Guåhån.

San Dionisio was its parish church and cemetery. Humåtak also served as a waystation for the Manila galleon that connected Acapulco (New Spain) and Manila (the Philippines) until 1815. As a result, Humåtak is one of the places in Guåhån, and indeed in all of Oceania, with most well-preserved architectural heritage from the colonial period.

Humåtak’ s residents are deeply involved in participating and/or supporting efforts to investigate and preserve their rich heritage.

Excavations at San Dionisio commenced in 2017 as part of this effort, and through a collaborative partnership of the Guåhån Preservation Trust-GPT (Inangokkon Inadahi Guahan), Universitat Pompeu Fabra-UPF, University of Hawai’i-Mānoa-UH and the Humåtak mayor’s office and in the long run, the University of Barcelona y and the Autonomous University of Madrid have also joined ABERIGUA to develop fieldwork within the framework of community archaeology.

Gabriella Topasna and Tyler Aguon explain San Dionisio’s history to visitors

San Dionisio

San Dionisio was established within the 17th century global expansion of Jesuits missions. It began to be built in 1680, and was dedicated in 1681. This early San Dionisio may have been a wood and thatch structure, which, like many other buildings in Guåhån, was destroyed on several occasions by a combination of natural and human-driven events, such as conflict and native resistance. While it was most likely constructed following the Latte tradition, stone was already used in 1715 and, most possibly, it acquired increasing monumentality during its subsequent reconstructions. We have documented multiple episodes of reconstruction/maintenance and pavements that predate the impressive two column structure that frames the Main Altar.

2017 excavations at San Dionisio

We have documented multiple episodes of reconstruction/maintenance and pavements that predate the impressive two column structure that frames the Main Altar.

The actual remains of San Dionisio are coral masonry walls with a mortar facing that is 2-3 cm in thickness. The standing walls convey a strong feeling of massiveness. In 1939 a new San Dionisio church was constructed several meters to the west, and directly on top of the remains of the Governor’s residence. While this event constrains our ability to conduct archaeological investigations at the Palasyo, it did enhance the preservation of the earlier San Dionisio building.

The cemetery

The advent of the mission and the introduction of Christianity precluded the traditional use of native dwellings for housing deceased ancestors. Funerary spaces would become more clearly differentiated and located in close proximity to the church, a novel building that emerged as a new locus of community life and community death. This process, however, was not always smooth. The Spanish sources, for instance, mention how difficult it was to bury Kepuha — one of the main chiefs at Hagåtña — in the church. They also describe how Jesuits burnt native idols at Pigpug and obliged its locals to re-bury their ancestor’s skulls.

Within ABERIGUA we are also investigating cultural continuities within funerary practices.

Kepuha’s statute in Hagåtña, Guåhån

ABERIGUA’s excavations

Our excavations at San Dionisio have been the first multi-year program of systemic archaeological excavation in the site.

To date, we have completed three archaeological field seasons (2017-2019). Our goals were to attain a better understanding of the beginnings of the colonial mission system in Guåhån, its evolution over time, and the impacts and involvement of the local native population. In addition to exploring the cultural dynamics that prevailed at San Dionisio, we sought to examine questions regarding the technology of buildings and their related activities, especially as it relates to the construction, reconstruction and periodic maintenance of the church.

Such activities, for example, would have entailed the procurement of the various construction materials (e.g., coral headstones, lime, nails, glass or, among others, ceramic construction materials) that we have recovered during the excavation.

San Dionisio building materials

Excavation units and Results to date

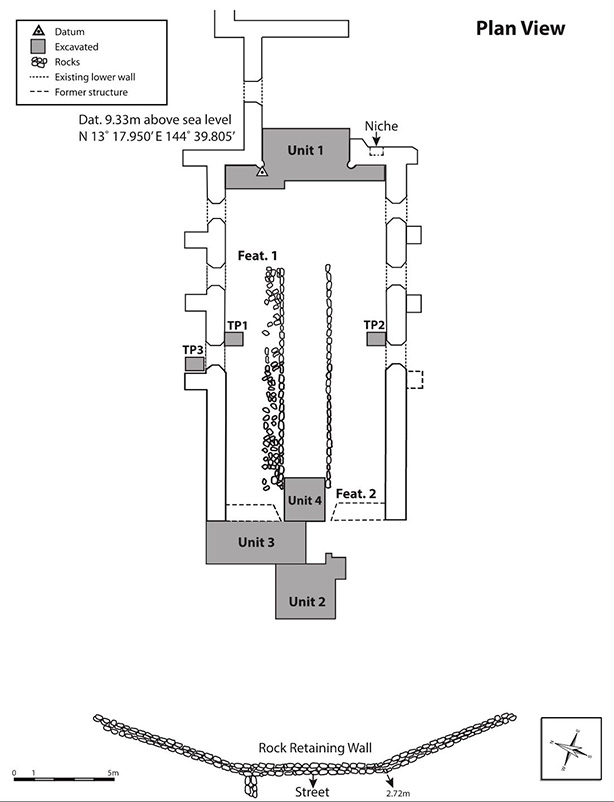

Plan view and location of excavation units in San Dionisio

To investigate these previous and other research questions we established a real excavation units and test pits.

Unit 1 was located in the area of the main altar. The most visible and impressive feature was part of the arched structure with two carved columns that would have framed the access entry to the presbytery. Unit 2 was opened to investigate a potential cemetery, which co-occurred with the remains of a pavement of large coral slabs. Unit 3 was designed to achieve a better understanding of the church’s façade and its connection with the burial area. The area which is closer to the main façade seems to be reserved for newborns, infants and toddlers. Unit 4 was established to investigate the area of the main gate.

A total of 15 primary burials and 15 “bone assemblages” have been documented in Units 2 and 3. The osteoarchaeological analysis is currently under study.

Pit burials in front of the main façade

Material Culture

Iron nails

Together with human osteoarchaeological remains we have uncovered an assemblage of materials whose study will be fundamental to evaluating our research questions. Colonial-style artifacts (e.g., ceramic building material, iron nails, galleon’s amphorae, bone buttons) as well as Latte-style artefacts (e.g., sling stones, shell beads, pottery) have been recovered.

Additionally, we also recovered an assemblage of recent materials in the surface layers. Of special significance are post WWII marbles — given to children by the Red Cross — and a Japanese canteen. These materials illuminate more recent activities in the vicinity of the building following its abandonment during the post-Spanish period.

Within the ABERIGUA project, we have initiated various lines of research to investigate how the Jesuit missions impacted the routines of CHamoru everyday life.

We realize that ongoing study of the material culture that we recovered will permit us to develop a deeper understanding of the alteration of earlier cultural routines that were interrupted by the mission. While this research may confirm that many earlier traditions were altered in profound ways, we anticipate that many later practices were still rooted in local traditions, like the use of coral in architecture. Native knowledge of coral reefs, for example, was likely instrumental in the construction of the church with coral blocks in the early 18th century. Notably, we have documented coral blocks in the church walls that could have been recycled from surrounding Latte buildings, as they were in other colonial buildings.

Archaeological Assistants

Xavier Quinata, Samaria Quinata, Ben Quinata, Detra Santiago, Gabriella Topasna, Michaela Aguon, Tyler Aguon, Kiana Siguenza, Jaren Aguon, Troy Cruz, Kara Santiago, Nick Roberto, Glenn Quinata, Shirley Brooks, Cam Quinata, and Alonso Quinata have been San Dionisio’s “archaeological assistants”, the name they used to define their rol in the excavations.

Glenn Quinata compared excavating to “unwrapping” a present, and we invite you to unwrapp the video they created about ABERIGUA’s excavations.

We have shared together time, work, culture and fiesta.

To all of them Si Yu’us ma’åse’ and Biba!